I should be planning for the week right now, but inspiration struck.

I was listening to The Creative Weirdos, a podcast I learned about this morning. The host and his guests were discussing David Lynch and Twin Peaks. About an hour into the episode, they brought up Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity, an esoteric self-help book Lynch wrote roughly 15 years ago. In that book, Lynch talks about ideas and how they are basically fancy thoughts. He writes:

“An idea is a thought. It’s a thought that holds more than you think it does when you receive it. But in that first moment there is a spark. In a comic strip, if someone gets an idea, a light bulb goes on. It happens in an instant, just as in life. It would be great if the entire film came all at once, but it comes for me in fragments. That first fragment is like the Rosetta Stone. It’s the piece of the puzzle that indicates the rest. It’s a hopeful puzzle piece.”

This description of an idea reminded me of something. My students.

Any students, for that matter.

And really, any person.

Each kid is a spark. A bright, shiny being filled with potential. The puzzle piece that, as Lynch eloquently puts it, “… indicates the rest.”

We educators spend our days working in our classrooms with anywhere from a dozen or so to upwards of 30 puzzle pieces. We examine their edges, looking for the best way to make our teaching fit them.

Some kids are corner pieces, with only a couple of options for helping them move forward with their learning. Some are surrounded by tabs, just waiting to latch onto something new. Others are surrounded by sockets, and they need an approach that will take the necessary step of attaching to them, rather than vice versa. And there are those that are a mix of tabs and sockets, attaching independently or needing support, depending on the subject.

If we’re successful, when June arrives, we have a classroom full of partially completed puzzles. Partially completed because the process continues when the next school year arrives. If we’ve well and truly done our job, we’ve created puzzles that will never stop growing, even long after diplomas and degrees have been earned.

Lynch calls these initial puzzle pieces “hopeful,” and I agree.

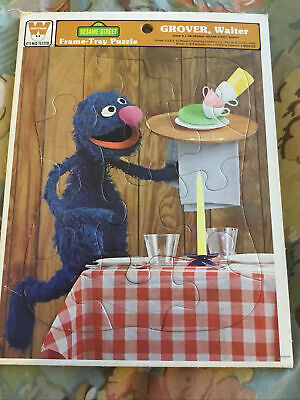

Some of those hopeful pieces might grow by several dozens of pieces as the months go by. Others by only a few. And that’s ok. Not every puzzle is 1,000 pieces. One of my favorite puzzles when I was a kid was a 12-piece puzzle of Sesame Street’s Grover as a waiter. Not the most difficult puzzle in the world, but it was a heck of a lot of fun to put together, and for 5-year-old me, it was plenty challenging.

The thing with puzzle pieces is, at the end of the day, did we try to find a starting point, or did we take a look, decide it wasn’t worth the effort, and toss it back in the box? It’s a choice we make each and every day with each and every one of our students.

Some puzzles are harder than others. That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be put together.